Why was this thread started?

You know why. Look who the OP is.

Why was this thread started?

Why was this thread started?

I would explain it by saying that Americans own way more guns than people living in other countries

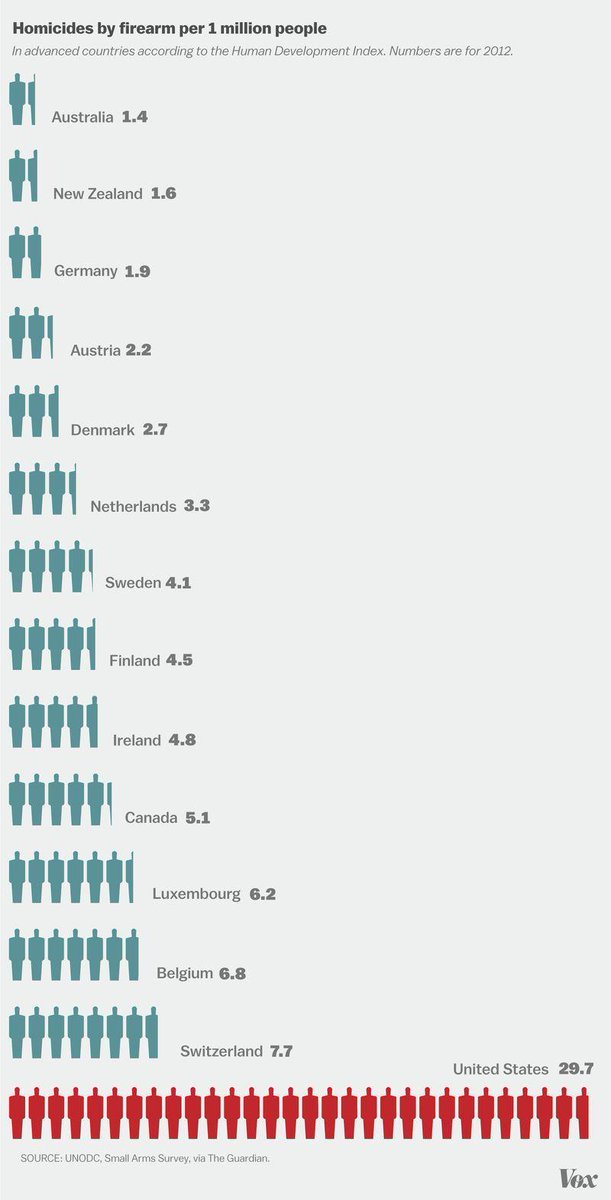

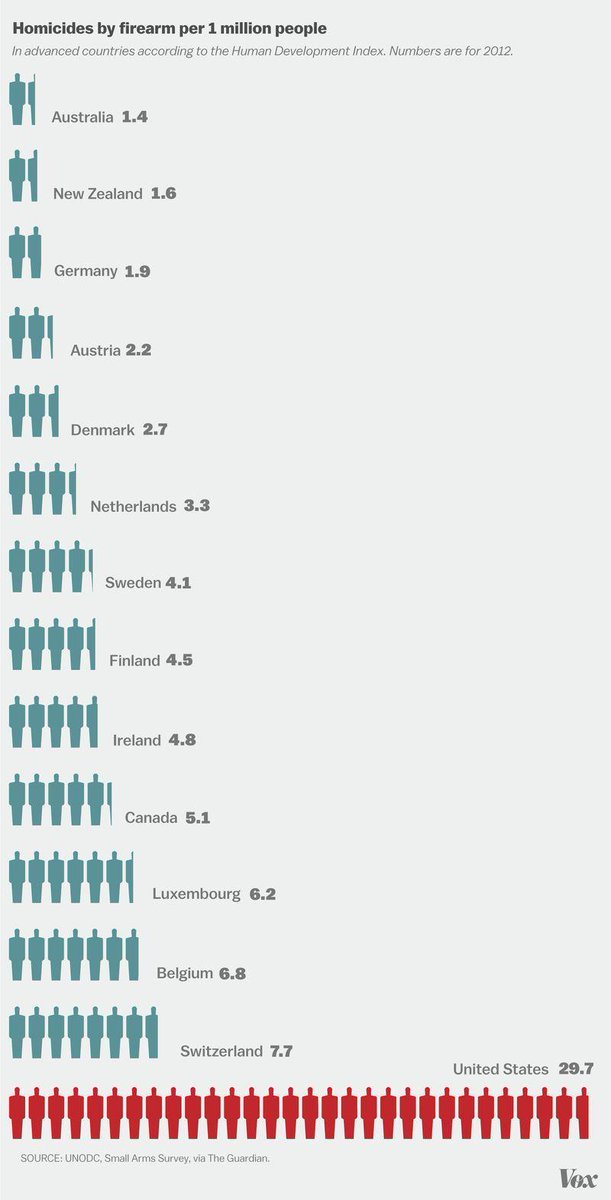

I call BS, show me a graph of homicides per 1 million, regardless of what weapon was used to commit the crime.

anyone want to take a stab at explaining this?

I don't see a pretty chart created, but if you look up homicides per 100,000 people, America sits around 5. The highest other country on that list that I saw was like 1.6

I call BS, show me a graph of homicides per 1 million, regardless of what weapon was used to commit the crime.

Jonathan Kay: America's firearms culture forged by paranoia, racism and civil rights unrest

Republish Reprint

Jonathan Kay | August 2, 2014 12:23 AM ET

This week, the United States Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit upheld a 2011 Florida law that makes it illegal for doctors to ask parents if they keep a gun in their house — notwithstanding the fact that the presence of such a weapon is, according to one expert, “43 times more likely to be involved in the death of a member of the household than to be used in self-defence.”

Earlier this year, Georgia Governor Nathan Deal signed legislation known to critics as the “guns everywhere bill.” The law allows Georgia residents to carry guns into bars, most government buildings and gun-friendly churches. On the same day, Kansas Governor Sam Brownback signed a bill that would ban any local government from enforcing ordinances that restrict the open carrying of firearms. “Kansans have long believed the right to bear arms is a constitutional right,” he explained.

Meanwhile, members of a group called “Open Carry Texas” are marching proudly through busy stores and parking lots armed with assault rifles, small children in tow. In one iconic photo, an overweight man with a massive gun slung over his shoulder stands in front of a rack of baby toys at Target, drinking from a bottle of water. According to Open Carry Texas founder CJ Grisham, such stunts will help show Americans that liberals’ collective fear of guns is “irrational.”

Well then colour me irrational. And colour all of Canada irrational, too — even the conservative parts. There is a fine line between responsible gun-rights advocacy and America’s GOP-enabled Yosemite Sam gun-cult carnival — and I feel comfortable drawing that line around the diaper section of my local big-box store.

Make no mistake: Millions of Canadians value their guns. Since the gun-control excesses of the Chrétien years, our hunters, target shooters and collectors have been fighting back against excessive bureaucracy, as epitomized by the widely derided (and now gratifyingly defunct) long-gun registry. But for these Canadians, guns are tools, not objects of psycho-sexual religious veneration. There is no Canadian equivalent of Charlton Heston, who declared at the NRA’s 2000 annual meeting that “Sacred stuff resides in that wooden stock and blue steel, something that gives the most common man the most uncommon of freedoms … When ordinary hands can possess such an extraordinary instrument, that symbolizes the full measure of human dignity and liberty.”

To a Canadian shooter, a gun is something used to kill gophers. To his American equivalent of the Heston school, it’s a sort of giant wand for killing Voldemort. How, exactly, did this massive gulf open up in our perception of “that wooden stock and blue steel”?

The common answer is: The Second Amendment to the United States Constitution, which states, “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” Canada has no equivalent to this: If our legislators had a mind to do so, they could ban guns outright tomorrow with the stroke of a pen.

But this focus on the Second Amendment can be misleading — because it presumes that America’s constitution created its gun culture. In fact, as legal scholar Michael Waldman argues in a fine new book, The Second Amendment: A Biography, the opposite is true: Since the late 18th-century, it has been America’s evolving cultural attitudes toward war, state sovereignty, race and crime that have shaped and reshaped the country’s interpretation of the Second Amendment.

America’s Founding Fathers thought a lot about guns, but primarily in the narrow context of defending themselves from Brits, Indians and other outside threats. One of the great controversies of the late 18th century was whether military might should reside primarily in the form of ad hoc citizen militias staffed by farmers, innkeepers and assorted yeomen called up for short-term duty — or a standing army staffed by full-time professional soldiers, which many Americans believed might become an instrument of tyranny. The wording of the Second Amendment reflects that anxiety.

Records of the House of Representatives debates on the arms amendment show that “the purpose of the right of ‘keeping arms’ was to strengthen the militia and thus ward off the spectre of an army,” Waldman writes. “Twelve congressmen joined the debate. None mentioned a private right to bear arms for self-defense, hunting or for any purpose other than joining the militia.”

And, indeed, this militia-centric interpretation of the Second Amendment was the dominant one in courts and intellectual circles until the late 20th century, when the gun lobby and its allies pushed a revisionist narrative that culminated with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in the 2008 case of District of Columbia v. Heller, which, for the first time in more than two centuries of American jurisprudence, declared that the Second Amendment protects an individual’s right to use guns for (otherwise lawful) self-defense. Conservative Justice Antonin Scalia, who authored the Court’s opinion, considers is some of his finest work.

But I’m getting ahead of myself: In the two centuries between James Madison and Antonin Scalia, America’s historical gun narrative took several important turns.

During the Civil War and the Reconstruction era that followed it, white American men in the south, including returning Civil War veterans, held onto their guns dearly as a means to protect them from the emancipated black hordes. Meanwhile, blacks themselves availed themselves of their newfound gun-ownership rights to defend themselves from white mobs. The paranoid, racist atmosphere that suffused this period in American life lies behind the southern states’ especially acute obsession with that “extraordinary instrument.”

But even then, the urban-rural divide on guns was growing: In America’s teeming northern cities, crime epidemics caused citizens to cry out for what we would now recognize as modern gun-control laws. In 1911, New York State passed the Sullivan Act, which required state residents to acquire permits for concealable weapons. At the time, no one claimed the Second Amendment had anything to say about such laws.

In the 1930s, Franklin Roosevelt took the gun-control campaign to the federal level, in response to the wave of World War I-style machine guns being fielded by mobsters such as George “machine gun” Kelly and Al Capone. The crackdown was hugely popular, and constitutionally kosher: In a 1934 case, U.S. v. Miller, the U.S. Supreme Court confirmed the then-well-established principle that the Second Amendment was all about well-regulated militias. When a representative from the National Rifle Association was asked by a Congressman what he thought of the federal machine-gun ban, he replied “I do not believe in the general promiscuous toting of guns. I think it should be sharply restricted and only under licenses.” As for the question of whether such gun-control laws might violate the Constitution, the NRA official responded: “I have not given it any study from that point of view.”

Had America’s attitudes to guns been frozen during this period, Canada and the United States might now have roughly similar attitudes; and a shopper would be able to buy a teddy bear in Texas without running into a random hothead with an assault rifle. But the Cold War years changed things, especially the civil-rights violence, race riots and campus turbulence of the 1960s. The idea that ordinary God-fearing Americans were under siege from the forces of chaos combined with the Red Scare to create the seeds of today’s Open Carry Texas-type extremism. In 1967, Guns & Ammo told readers that gun control was part of a plot hatched by “criminal-coddling do-gooders, borderline psychotics, as well as Communists and leftists who want to lead us into the one-world welfare state.”

After Washington Navy shooting leaves 13 dead, U.S. pundits argue whether they are allowed to argue gun control at all

By the Reagan era, these paranoid notions became part of the American conservative mainstream — the precursor to today’s GOP talking points about Barack Obama’s supposed schemes to take away Americans’ guns. As for the NRA, it morphed from a sportsmen’s club into a political organizational that warned its members of UN black helicopters and “jack-booted government thugs.” It also began funding legal scholars seeking inventive arguments for expanding Second Amendment protection to every weapon imaginable. With the Heller decision, they hit paydirt.

For Canadian readers, all of this helps explain why our gun culture is so moderate and civilized compared to its overheated American cousin. We never had a Civil War, nor the race paranoia associated with it. Our Red Scare was more muted, our civil-rights struggles more docile, our crime waves less deadly, and our population less libertarian. Perhaps more importantly, we Canadians are a less Evangelical people, and so have less tolerance for apocalyptic narratives and action-movie reveries about “sacred stuff” residing in this or that mass-produced weapon.

This is not some abstract history lesson. It has flesh-and-blood consequences: If Canada’s homicide rate were as high as America’s, about a thousand more Canadians would be murdered every year. That they live instead of die is due in no small measure to our particularly “irrational” Canadian willingness to find ways of limiting access to guns, short of having them removed from our cold, dead hands.

National Post

You know why. Look who the OP is.

Why was this thread started?

Why do liberals hate guns because republican states are for them?