You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Climate Change Thread

- Thread starter str8line

- Start date

Red

Well-Known Member

OK, back to facts….So much unambiguous evidence of rapidly warming oceans, yet we still have ignorant nitwits, especially among Trump supporters, carrying on about how we are not seeing what we are seeing. Led by Trump of course: “climate change is a hoax”. That’s like saying the sun rises in the west, and passing a law declaring the sun will no longer rise in the East. There is no denying global warming, caused by humans, at this stage of the game. And since it’s happening, and it’s harmful to humans(not to mention all life on Earth), Trump is truly guilty of “crimes against humanity” in adopting his falsehoods, and insisting his Big Lie of “global warming is a hoax” will be our official position.

We need to remember something. It’s not mentioned often, what with all the other daily outrages, but it’s a truly important point to make, since it establishes the most accurate assessment of what Trump represents this. It’s impirtant to realize this:

DONALD TRUMP IS THE ENEMY OF ALL LIFE ON EARTH. It’s that simple, that fundamental. He is clearly not only the worst president in our nation’s history, he is truly one of the most EVIL men alive today. Future generations will universally recognize this fact.

Donald Trump puts fossil fuel industry profits above life on Earth. Profits supersede human health, human survival, the survival of many forms of life, all our fellow travelers on this precious planet. That is EVIL. It ain’t over yet, this national nightmare, but make no mistake: history will remember Trump as one of the most evil human beings alive in our era, doing damage that all future generations will recognize as EVIL, even as misguided and delusional fanboys of Trump demonstrate how easy it is for humans to be stupid, because their weak minds see only what they want to see…..

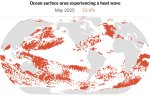

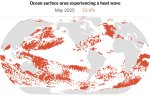

In 2023, the world’s oceans endured the most extreme and prolonged marine heatwaves in recorded history, with some lasting over 500 days and covering nearly the entire globe.

These unprecedented temperature spikes devastated coral reefs, disrupted marine food chains, and threatened global fisheries.

Such episodes can cause serious harm to ocean life, triggering widespread coral bleaching and large-scale die-offs. They also threaten economies by disrupting fishing and aquaculture. Experts widely agree that human-driven climate change is causing both the frequency and severity of MHWs to rise sharply.

To investigate, Tianyun Dong and colleagues conducted a detailed global study using a combination of satellite data and ocean reanalysis, including high-resolution information from the ECCO2 (Estimating the Circulation and Climate of the Ocean-Phase II) project.

ca.news.yahoo.com

ca.news.yahoo.com

www.wltx.com

www.wltx.com

We need to remember something. It’s not mentioned often, what with all the other daily outrages, but it’s a truly important point to make, since it establishes the most accurate assessment of what Trump represents this. It’s impirtant to realize this:

DONALD TRUMP IS THE ENEMY OF ALL LIFE ON EARTH. It’s that simple, that fundamental. He is clearly not only the worst president in our nation’s history, he is truly one of the most EVIL men alive today. Future generations will universally recognize this fact.

Donald Trump puts fossil fuel industry profits above life on Earth. Profits supersede human health, human survival, the survival of many forms of life, all our fellow travelers on this precious planet. That is EVIL. It ain’t over yet, this national nightmare, but make no mistake: history will remember Trump as one of the most evil human beings alive in our era, doing damage that all future generations will recognize as EVIL, even as misguided and delusional fanboys of Trump demonstrate how easy it is for humans to be stupid, because their weak minds see only what they want to see…..

Earth’s Oceans Are Boiling. And It’s Worse Than We Thought

Marine heatwaves engulfed 96% of the world’s oceans in 2023, breaking records for duration, intensity, and scale. Scientists warn these events could be early signs of a destabilizing climate system.

scitechdaily.com

In 2023, the world’s oceans endured the most extreme and prolonged marine heatwaves in recorded history, with some lasting over 500 days and covering nearly the entire globe.

These unprecedented temperature spikes devastated coral reefs, disrupted marine food chains, and threatened global fisheries.

Unprecedented Ocean Heat in 2023

The marine heatwaves (MHWs) that swept across the globe in 2023 were unlike anything seen before in terms of strength, persistence, and size, according to a new scientific analysis. Researchers have identified the regional factors behind these extraordinary events and linked them to broader shifts in Earth’s climate system. Their work also raises concerns that the planet may be edging toward a climate tipping point. MHWs are extended periods when ocean temperatures soar far above normal levels.Such episodes can cause serious harm to ocean life, triggering widespread coral bleaching and large-scale die-offs. They also threaten economies by disrupting fishing and aquaculture. Experts widely agree that human-driven climate change is causing both the frequency and severity of MHWs to rise sharply.

A Global Wave of Extremes

In 2023, vast stretches of the North Atlantic, Tropical Pacific, South Pacific, and North Pacific were gripped by extreme MHWs. While the impacts were clear, the precise causes behind the timing, duration, and strengthening of these widespread events have not been fully understood.To investigate, Tianyun Dong and colleagues conducted a detailed global study using a combination of satellite data and ocean reanalysis, including high-resolution information from the ECCO2 (Estimating the Circulation and Climate of the Ocean-Phase II) project.

The world’s longest marine heat wave upended ocean life across the Pacific

The multi-year heat wave nicknamed ‘The Blob’ impacted thousands of kilometres of marine ecosystems from Alaska to Baja California.

Oceans heating at record pace, threatening U.S. coasts and marine life

Oceans are heating up at unprecedented rates, posing threats to hurricanes and marine life.

Last edited:

Red

Well-Known Member

Scientists recognize the crimes being committed by Trump….Imagine thinking Trump somehow knows more than climate scientists? This is a totalitarian attempting to rewrite history. Just as he has done with our political history over the past 10 years, twisted into a number of Orwellian fascist Big Lies, so he is doing the same with climate science. Rewriting past climate reports to reflect his political preferences over good science! This is why he is guilty of crimes against humanity when he ignores a warming planet……

www.theguardian.com

www.theguardian.com

The US energy secretary, Chris Wright, is facing growing criticism from scientists who say their “worst fears” were realized when Wright revealed that the Trump administration would “update” the US’s premier climate crisis reports.

Wright, a former oil and gas executive, told CNN’s Kaitlin Collins earlier this week that the administration was reviewing national climate assessment reports published by past governments.

Produced by scientists and peer-reviewed, there have been five national climate assessment (NCA) reports since 2000 and they are considered the gold standard report of global heating and its impacts on human health, agriculture, water supplies and air pollution.

“We’re reviewing them, and we will come out with updated reports on those and with comments on those reports,” said Wright, who is one of the main supporters of the administration’s “drill, baby, drill” agenda to boost fossil fuels, which are the primary cause of the climate crisis.

www.eenews.net

www.eenews.net

Make no mistake. These actions are criminal. Undermining good, solid science to promote policy that represents encouraging harm to future generations from global warming is a crime. Against the human race. Against all life on Earth.

thebulletin.org

thebulletin.org

Esteemed climate scientist Michael Mann said the report was akin to the result he would expect “if you took a chat bot and you trained it on the top 10 fossil fuel industry-funded climate denier websites.”

The Energy Department published the report hours after the EPA announced a plan to roll back the “endangerment finding,” a seminal ruling that provided the legal basis for the agency to regulate climate-heating pollution under the Clean Air Act. If finalized, the move would topple virtually all US climate regulation.

In a Fox News interview, Wright claimed the report pushes back on the “cancel culture Orwellian squelching of science.” But Naomi Oreskes, a history of science professor at Harvard University and expert in climate misinformation, said its true purpose is to “justify what is a scientifically unjustifiable failure to regulate fossil fuels.”

“Science is the basis for climate regulation, so now they are trying to replace legitimate science with pseudoscience,” she said.

————————————————————————————————————————————

Individuals who undermine good science this way are themselves supporting crimes against the human race, and all life on Earth. And they proudly showcase their ignorance, be they trolls, or be they manipulative fascists.

Scientists decry Trump energy chief’s plan to ‘update’ climate reports: ‘Exactly what Stalin did’

Ex-fossil fuel executive Chris Wright said administration is reviewing national assessments made by past governments

The US energy secretary, Chris Wright, is facing growing criticism from scientists who say their “worst fears” were realized when Wright revealed that the Trump administration would “update” the US’s premier climate crisis reports.

Wright, a former oil and gas executive, told CNN’s Kaitlin Collins earlier this week that the administration was reviewing national climate assessment reports published by past governments.

Produced by scientists and peer-reviewed, there have been five national climate assessment (NCA) reports since 2000 and they are considered the gold standard report of global heating and its impacts on human health, agriculture, water supplies and air pollution.

“We’re reviewing them, and we will come out with updated reports on those and with comments on those reports,” said Wright, who is one of the main supporters of the administration’s “drill, baby, drill” agenda to boost fossil fuels, which are the primary cause of the climate crisis.

How Chris Wright recruited a team to upend climate science

The Energy secretary handpicked climate contrarians to write a report that EPA is using to undermine U.S. regulation of greenhouse gases.

Make no mistake. These actions are criminal. Undermining good, solid science to promote policy that represents encouraging harm to future generations from global warming is a crime. Against the human race. Against all life on Earth.

Trump administration climate report a ‘farce,’ scientists say

The report, which is being used to justify the rollback of a huge number of climate regulations, is full of misinformation—with many claims based on long-debunked research.

Esteemed climate scientist Michael Mann said the report was akin to the result he would expect “if you took a chat bot and you trained it on the top 10 fossil fuel industry-funded climate denier websites.”

The Energy Department published the report hours after the EPA announced a plan to roll back the “endangerment finding,” a seminal ruling that provided the legal basis for the agency to regulate climate-heating pollution under the Clean Air Act. If finalized, the move would topple virtually all US climate regulation.

In a Fox News interview, Wright claimed the report pushes back on the “cancel culture Orwellian squelching of science.” But Naomi Oreskes, a history of science professor at Harvard University and expert in climate misinformation, said its true purpose is to “justify what is a scientifically unjustifiable failure to regulate fossil fuels.”

“Science is the basis for climate regulation, so now they are trying to replace legitimate science with pseudoscience,” she said.

————————————————————————————————————————————

Individuals who undermine good science this way are themselves supporting crimes against the human race, and all life on Earth. And they proudly showcase their ignorance, be they trolls, or be they manipulative fascists.

Last edited:

PJF

Well-Known Member

Red

Well-Known Member

Something different. The Kogi people of Columbia. I believe we can learn a great deal from “primitive” societies. The Kogi decided to speak up for the planet Earth a number of years ago, and sought ways to convey their ecological warning to “younger brother”, as they, the “elder brother” refer to we humans of the West. Traditional understanding is important. After all, if mankind did decide to engage in nuclear war in the future, it’s the uncontacted and isolated traditional people of the world that will have the best chance of surviving.

www.artshelp.com

www.artshelp.com

The first Kogi film. We learn that they train their shamans, their spiritual leaders/healers, by raising them in a cave for years, following birth, and only later introduce them to the outside world for the first time. What a trip that must be…

And Aluna: the Kogi warning to mankind:

www.templeton.org

www.templeton.org

An ethic of kinship

Although a causal relationship between spending time in nature and environmental action hasn’t been clearly demonstrated, it makes intuitive sense that someone with a spiritual connection to nature would be motivated to try to care for it. That link is something Ulishney hopes to study directly in her research. “This is one of the things I’m really interested in: Is there at least a correlation between people who would express a strong sense of nature spirituality and concrete actions that they’re doing to address the ecological crisis?”

Loorz believes there is. “You hear people say all the time that beneath the climate crisis, it’s a spiritual problem, right? Yes, we’ve got all these technological and legal problems—but underneath it is a spiritual problem, a worldview of disconnection.”

This worldview of disconnection, she says, leads to a lack of care for other species, which in turn opens the doorway to abuse and exploitation. Her hope for Wild Churches, and for anyone who finds spiritual renewal through communion with nature, is to recognize and reinvigorate the kinship between humans and all other life. To know, and eventually to love, the other members of our shared home.

“The beloved community extends beyond our own species,” says Loorz. “To think that it doesn’t is damaging not only to the earth, but to our own selves and our own spirituality in ways that we’re just awakening to again after being disconnected for so many generations.”

Aluna: The Kogi’s ecological warning to save the world

> You cannot be human without understanding the natural order of the territory. —Hate Kulchavita Boñe Aluna is a 2012 documentary by the British filmmaker Alan Ereira, produced as a consequence of the previous documentary, From The Heart of The World...

The first Kogi film. We learn that they train their shamans, their spiritual leaders/healers, by raising them in a cave for years, following birth, and only later introduce them to the outside world for the first time. What a trip that must be…

And Aluna: the Kogi warning to mankind:

Speak to the Earth, and It Will Teach You

Spiritual energy can be encountered in the mountains, a grove of trees, or a river, and a relationship with the natural world is essential to their spiritual lives.

An ethic of kinship

Although a causal relationship between spending time in nature and environmental action hasn’t been clearly demonstrated, it makes intuitive sense that someone with a spiritual connection to nature would be motivated to try to care for it. That link is something Ulishney hopes to study directly in her research. “This is one of the things I’m really interested in: Is there at least a correlation between people who would express a strong sense of nature spirituality and concrete actions that they’re doing to address the ecological crisis?”

Loorz believes there is. “You hear people say all the time that beneath the climate crisis, it’s a spiritual problem, right? Yes, we’ve got all these technological and legal problems—but underneath it is a spiritual problem, a worldview of disconnection.”

This worldview of disconnection, she says, leads to a lack of care for other species, which in turn opens the doorway to abuse and exploitation. Her hope for Wild Churches, and for anyone who finds spiritual renewal through communion with nature, is to recognize and reinvigorate the kinship between humans and all other life. To know, and eventually to love, the other members of our shared home.

“The beloved community extends beyond our own species,” says Loorz. “To think that it doesn’t is damaging not only to the earth, but to our own selves and our own spirituality in ways that we’re just awakening to again after being disconnected for so many generations.”

Last edited:

Red

Well-Known Member

‘No country is safe’: deadly Nordic heatwave supercharged by climate crisis, scientists say

Historically cool nations saw hospitals overheating and surge in drownings, wildfires and toxic algal blooms

The prolonged Nordic heatwave in July was supercharged by the climate crisis and shows “no country is safe from climate change”, scientists say.

Norway, Sweden and Finland have historically cool climates but were hit by soaring temperatures, including a record run of 22 days above 30C (86F) in Finland. Sweden endured 10 straight days of “tropical nights”, when temperatures did not fall below 20C (68F).

Global heating, caused by the burning of fossil fuels, made the heatwave at least 10 times more likely and 2C hotter, the scientists said. Some of the weather data and climate models used in their analysis indicated the heatwave would have been impossible without human-caused climate breakdown.

The heat had widespread effects, with hospitals overheating and overcrowding and some forced to cancel planned surgery. At least 60 people drowned as outdoor swimming increased, while toxic algal blooms flourished in seas and lakes.

Hundreds of wildfires burned in forests and people were reported fainting at holiday-season events. In the last major heatwave in the region, in 2018, 750 people died early in Sweden alone, and scientists anticipate a similar toll once the data is processed.

Wildlife was also affected, especially the Scandinavian peninsula’s famous reindeer. Some animals died in the heat and others entered towns seeking shade. Drivers were warned that reindeer could seek to cool down in road tunnels.

Much of the northern hemisphere has experienced heatwaves in recent weeks. This includes the UK, Spain and Croatia, where wildfire destruction is almost double the 20-year average, and the US, Japan and South Korea. Scientists are certain that the climate crisis has intensified this extreme weather.

Prof Friederike Otto, a climatologist at Imperial College London who leads the World Weather Attribution (WWA) collaboration, which did the Nordic analysis, said: “Even relatively cold Scandinavian countries are facing dangerous heatwaves today with 1.3C of warming – no country is safe from climate change.

“Burning oil, gas, and coal is killing people today. Fossil fuels are supercharging extreme weather and to stop the climate from becoming more dangerous, we need to stop burning them and shift to renewable energy.”

Heatwaves such as the one in Scandinavia will become another five times more frequent by 2100 if global heating reaches 2.6C, which is the trajectory today.

PJF

Well-Known Member

Climate change alarmists are so full of crap.

View: https://x.com/RussLarson/status/1957112571263103427?t=eLd-IqLLuiVcwNHdqXesvw&s=19

View: https://x.com/RussLarson/status/1957112571263103427?t=eLd-IqLLuiVcwNHdqXesvw&s=19

Red

Well-Known Member

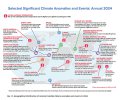

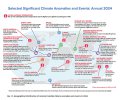

The International Climate Report for 2024 has been released. More than 600 credentialed scientists contributed. It’s grim….

On a side note, something I noticed yesterday, while tracking hurricane Erin, that it had increased briefly to a Category 5. Turns out that was the fastest an Atlantic hurricane had ever gone from cat 1 to cat 5. We can be 100% certain that was due to the warming Atlantic, brought about by human caused global warming. Climate change is 100% proven. There is no longer any point in claiming otherwise, as Trump insists. What Trump is doing is criminal.

.

According to the 35th annual State of the Climate report, greenhouse gas concentrations, the global temperature across land and oceans, global sea level, and ocean heat content all reached record highs in 2024, and glaciers lost the most ice of any year on record.

The international review of the world’s climate, published by the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (BAMS), is based this year on contributions from 589 scientists in 58 countries. For decades, the State of the Climate has provided the most comprehensive annual update on Earth’s climate — illuminating not only key indicators like global CO2 but also notable weather events, regional phenomena, and other data collected by environmental monitoring stations and instruments located on land, water, and ice, as well as in space.

“The State of the Climate report is an annual scientific landmark,” says American Meteorological Society President David J. Stensrud. “It is a truly global effort, in which hundreds of researchers from universities, government agencies, and more come together to provide a careful, rigorously peer-reviewed report on our planet’s climate. High-quality observations and findings from all over the world are incorporated, underscoring the vital importance of observations to monitor, and climate science to understand, our environment. The results affirm the reality of our changing climate, with 2024 global temperatures reaching record highs."

Notable findings from the international report include:

www.earth.com

www.earth.com

www.splinter.com

www.splinter.com

www.dailymail.co.uk

www.dailymail.co.uk

www.yahoo.com

www.yahoo.com

You’d have to be living on another planet not to notice this effect of global warming:

“The assessment also highlighted that the world's water cycle continues to intensify. "The global atmosphere contained the largest amount of water vapor on record, with over one-fifth of the globe recording their highest values in 2024," it stated. "Extreme rainfall, as characterized by the annual maximum daily rainfall over land, was the wettest on record."

On a side note, something I noticed yesterday, while tracking hurricane Erin, that it had increased briefly to a Category 5. Turns out that was the fastest an Atlantic hurricane had ever gone from cat 1 to cat 5. We can be 100% certain that was due to the warming Atlantic, brought about by human caused global warming. Climate change is 100% proven. There is no longer any point in claiming otherwise, as Trump insists. What Trump is doing is criminal.

.

According to the 35th annual State of the Climate report, greenhouse gas concentrations, the global temperature across land and oceans, global sea level, and ocean heat content all reached record highs in 2024, and glaciers lost the most ice of any year on record.

The international review of the world’s climate, published by the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (BAMS), is based this year on contributions from 589 scientists in 58 countries. For decades, the State of the Climate has provided the most comprehensive annual update on Earth’s climate — illuminating not only key indicators like global CO2 but also notable weather events, regional phenomena, and other data collected by environmental monitoring stations and instruments located on land, water, and ice, as well as in space.

“The State of the Climate report is an annual scientific landmark,” says American Meteorological Society President David J. Stensrud. “It is a truly global effort, in which hundreds of researchers from universities, government agencies, and more come together to provide a careful, rigorously peer-reviewed report on our planet’s climate. High-quality observations and findings from all over the world are incorporated, underscoring the vital importance of observations to monitor, and climate science to understand, our environment. The results affirm the reality of our changing climate, with 2024 global temperatures reaching record highs."

Notable findings from the international report include:

- Earth’s greenhouse gas concentrations were the highest on record. Carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, and nitrous oxide — Earth’s major atmospheric greenhouse gases — once again reached record-high concentrations in 2024. The globally averaged CO2 level reached 422.8±0.1 parts per million, a 52% increase from the pre-industrial level of ~278 ppm. Annual growth in global mean CO2 has increased from 0.6±0.1 ppm yr-1 in the early 1960s to an average of 2.4 ppm yr-1 during 2011–20. The growth from 2023 to 2024 was 3.4 ppm, equal with 2015/16 as the highest in the record since the 1960s.

- Record temperatures were notable across the globe. A new annual global surface temperature record was set for the second year in a row, with records dating back as far as the mid-1800s. A range of scientific analyses indicate that the annual global surface temperature was 1.13 to 1.30 degrees F (0.63 to 0.72 degrees C) above the 1991–2020 average. A strong El Niño that began in mid-2023 and ended in boreal spring 2024 contributed to the record warmth. The last time two consecutive years reached a new global surface temperature record was in 2015 and 2016, when a strong El Niño developed during the latter half of 2015 and dissipated by May 2016. All six major global temperature datasets used for analysis in the report agree that the last 10 years (2015–24) were the 10 warmest on record.

- The water cycle continued to intensify. Higher global temperatures impacted the water cycle. Water evaporation from land in the Northern Hemisphere reached one of the highest annual values on record. The global atmosphere contained the largest amount of water vapor on record, with over one-fifth of the globe recording their highest values in 2024. This far exceeded 2023, where only one-tenth of the globe experienced record-high values of total column water vapor. Precipitation was globally high; 2024 was the third-wettest year since records began in 1983. Extreme rainfall, as characterized by the annual maximum daily rainfall over land, was the wettest on record. In April, Dubai in the United Arab Emirates recorded 9.8 in (250 mm) of rain in 24 hours — nearly three times its annual average.

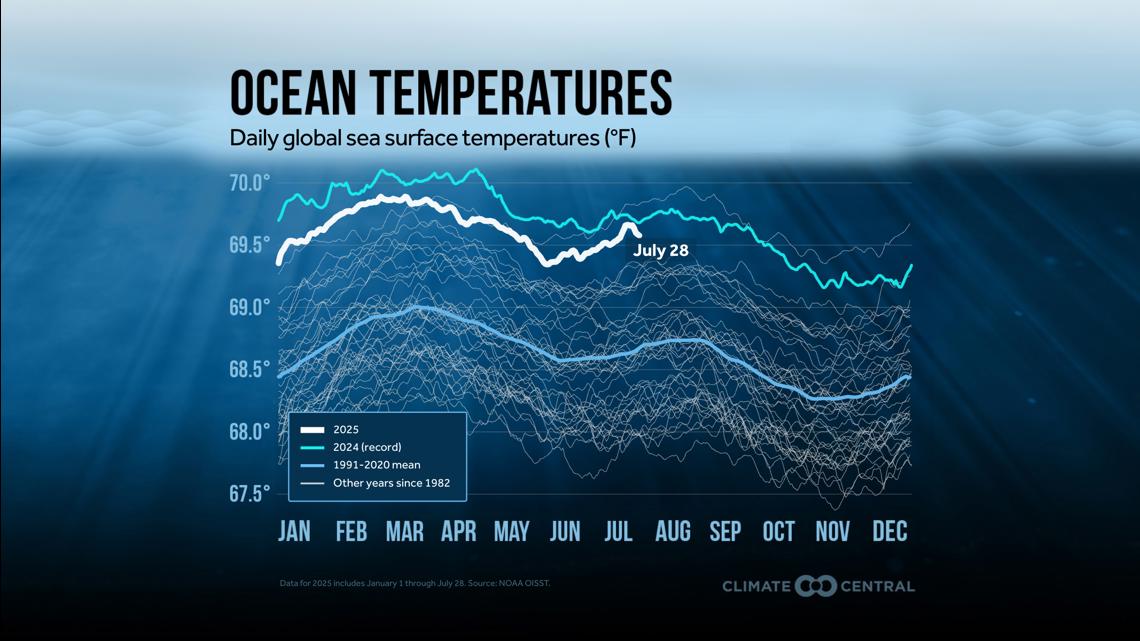

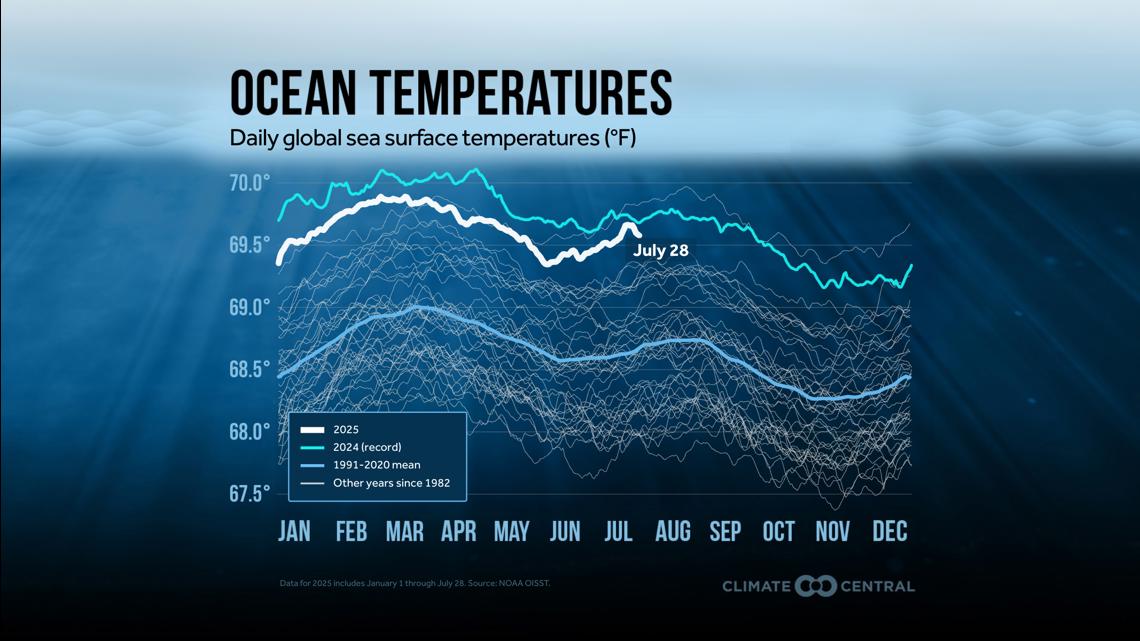

- El Niño conditions contributed to record-high sea surface temperatures. Strong El Niño conditions in the equatorial Pacific Ocean that emerged by the end of 2023 continued into early 2024, with neutral conditions returning in boreal spring. Daily globally averaged sea surface temperatures were at record-high levels from the beginning of 2024 until late June. The mean annual global sea surface temperature in 2024 was a record high, surpassing the previous record of 2023 by 0.11 of a degree F (0.06 of a degree C). Approximately 91% of the ocean surface experienced at least one marine heatwave in 2023, which is defined as sea surface temperatures in the warmest 10% of all recorded data in a particular location for at least five days. Only 26% of the ocean surface experienced at least one marine cold spell. The ocean experienced a record-high global average of 100 marine heatwave days and a new record low of nine marine cold spell days.

- Ocean heat and global sea level were the highest on record. Over the past half-century, the oceans have stored more than 90% of the excess energy trapped in Earth’s system by greenhouse gases and other factors. The global ocean heat content, measured from the ocean’s surface to a depth of 2000 m (approximately 6561 ft), continued to increase, and reached new record highs in 2024. Global mean sea level was a record high for the 13th consecutive year, reaching about 4.0 in (105.8 mm) above the average for 1993 when satellite altimetry measurements began. Warming oceans have contributed an average of 1.5±0.3 mm to the rise per year since 2005, while melt from ice sheets and glaciers have contributed an average of 2.1±0.4 mm during that same period.

- The Arctic saw near-record warmth. The Arctic had its second-warmest year in the 125-year record, with autumn (October to December) having been record warm. During the summer, an intense August heatwave brought all-time record-high temperatures to parts of the northwest North American Arctic, and record-high August monthly mean temperatures at Svalbard Airport reached more than 52°F (11°C). In September, temperatures above 86°F (30°C) were observed in Norway, marking the latest time of the year in the observational record that such high temperatures have occurred there. During the 2023/24 snow season, there were large differences in how long snow remained on the ground, from the shortest to date in the twenty-first century over parts of Canada to at or near the longest in this century in parts of the Nordic and Asian Arctic. The Arctic maximum sea ice extent in 2024 was the second smallest in the 46-year satellite record, while the minimum sea ice extent was the sixth smallest.

- Antarctica saw continued low sea ice. Following record lows in 2023, net sea ice extent was larger than last year but continued to be well below average during much of 2024. The Antarctic daily minimum and maximum sea ice extents for the year were each the second lowest on record behind 2023, marking a continuation of low and record-low sea ice extent since 2016.

- Glaciers around the world continued to melt. For the second consecutive year, all 58 global reference glaciers across five continents lost mass in 2024, resulting in the greatest average ice loss in the 55-year record. In South America, Venezuela became the first Andes country to register the loss of all glaciers. In Colombia, the Conejeras Glacier was declared extinct, joining the list of glaciers that have disappeared in recent years.

- Tropical cyclone activity was below average, but storms still set records around the globe. A total of 82 named tropical cyclones were observed during the Northern and Southern Hemispheres’ storm seasons, below the 1991–2020 average of 87 and equal to the number recorded in 2023. Many storms made landfall and some caused major damage. Hurricane Helene brought destruction from Florida to the southern Appalachian Mountains. The storm caused devastating record flooding that contributed to over 200 deaths, the most in the United States since Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Hurricane Milton impacted Florida’s Gulf Coast just 12 days after Helene affected the region, marking the shortest time between major (Category 3 or higher) hurricane landfalls in Florida. In the northwest Pacific basin, Super Typhoon Yagi became one of the most destructive storms to affect China and Vietnam in recent years, causing more than 800 fatalities.

State of the Climate 2024: Record heat and rising seas

2024 broke all climate records with highest temperatures, greenhouse gases, sea levels, and glacier loss ever.

The State of the Climate Is: Grim

Since 2007, Jezebel has been the Internet's most treasured source for everything celebrities, sex, and politics...with teeth.

Last year was the most HUMID on record, scientists warn

Climate change drove record levels of global humidity in 2024, posing a rising risk to people's health, a new report has warned.

International report confirms fears about growing global issue: 'The results affirm the reality'

"The ... report is an annual scientific landmark."

You’d have to be living on another planet not to notice this effect of global warming:

“The assessment also highlighted that the world's water cycle continues to intensify. "The global atmosphere contained the largest amount of water vapor on record, with over one-fifth of the globe recording their highest values in 2024," it stated. "Extreme rainfall, as characterized by the annual maximum daily rainfall over land, was the wettest on record."

Last edited:

Red

Well-Known Member

Scientists issue warning after observing Arctic phenomenon not seen in decades: 'A fundamental shift'

Locals are taking action.

Arctic glaciers face ‘terminal’ decline as microbes accelerate ice melt

Scientists in Svalbard in race to study polar microbes as global heating threatens fragile glacial ecosystems

Scientists stunned by what they saw during 2-week Arctic expedition: 'Shocking and surreal'

The researchers had to change course from their original plan.

"Standing in pools of water at the snout of the glacier, or on bare, green tundra, was shocking and surreal," researcher James Bradley told Meteored. "The thick snowpack covering the landscape vanished within days. The gear I packed felt like a relic from another climate."

Instead of their planned study, the researchers wrote about the effects of warming temperatures on Svalbard and the Arctic as a whole, with their work appearing in the journal Nature Communications.

"Winter warming in the Arctic has long reached melting point and is reshaping Arctic landscapes," the authors wrote. "These winter warming events are seen by many as anomalies, but this is the new Arctic."

Last edited:

Red

Well-Known Member

The relationship between ocean water temperatures and the intensity of hurricanes is probably one of the easiest components of global warming to understand. Since hurricanes draw their strength from the surface of the ocean, warmer waters=greater hurricane intensity. It’s common sense in that respect. Hurricane Erin has demonstrated that, as did last year’s Gulf coast hurricanes.

Hurricane Erin is whipping up the Atlantic Ocean at speeds over 100 miles per hour. The trajectory of the storm has it staying out to sea, though many effects will be felt close to shore and on land. And some of those effects are made worse by global warming.

Overnight on Friday, Hurricane Erin ratcheted up to a Category 5 storm, from a Category 1, becoming one of the top five most quickly intensifying hurricanes on record. As the planet warms, scientists say that rapidly intensifying hurricanes are becoming ever more likely.

"It’s a very easy set of dots to connect,” said Jim Kossin, who worked at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration as a hurricane specialist and climate scientist before he retired. “These rapid intensification events are linked pretty directly to that human fingerprint.”

According to the National Hurricane Center, rapid intensification is an increase in a storm’s sustained wind speeds of at least 35 miles per hour in a 24-hour period. Between Friday morning and Saturday morning, Hurricane Erin’s wind speeds increased by nearly 85 miles per hour, peaking at 161 mph.

Daniel Gilford, a climate scientist at Climate Central, a science communication nonprofit, likens hurricanes to the engine of a car. “They need some fuel source in order to spin, and the fuel source is the ocean surface,” he said. “So as the temperature of the ocean surface goes up, that adds more fuel that these storms can use to intensify.”

For over a century, greenhouse gases emitted by human activity have trapped heat inside the planet’s atmosphere. A recent streak of record-breaking temperatures crowned 2024 as the hottest year on record.

By May of 2024, super marine heat waves had turned nearly a quarter of the world’s ocean area into bath water, and this year’s Atlantic Ocean remains warmer than average. Earlier this summer, forecasters anticipated a busier than usual Atlantic hurricane season because of this lingering heat, along with other regional factors. Erin is the first named storm to become a hurricane this year.

As a storm moves across warm oceans, it gathers more fuel and becomes stronger. Because warmer air can hold more moisture, hurricanes in hotter conditions can also carry more rain.

According to Climate Central’s analysis of the storm, human-caused climate change made the warm water temperature around where Erin formed 90 percent more likely. The group’s early estimate, using a statistical model developed by NOAA, also found that the extra heat could drive 50 percent greater damage, like tidal erosion and flooding, to coastal areas.

Other features of storms have been exacerbated by the warming planet, too. As polar regions melt and sea levels rise, Dr. Gilford said, the rising tidal base line means that any coastal flooding from storms becomes correspondingly larger, too.

During Hurricane Sandy, floods were four inches deeper than they would have been without sea level rise, according to a Climate Central paper published in the journal Nature. “That doesn’t sound like a lot, but four inches could be the difference between over topping the bottom floor of a building or not,” he said.

After intensifying, Hurricane Erin grew a second larger eyewall, which is the meteorological term for the thick ring of clouds at the cyclone’s center. Hurricanes that go through an eyewall replacement cycle are larger in size but tend to have weaker wind speeds.

As of Wednesday afternoon, Hurricane Erin was 530 miles wide, an expanse that would smother New England. While the storm’s strongest winds aren’t expected to reach coastlines, the powerful waves and riptides that are generated will.

Faster intensification makes eyewall replacement more likely, Dr. Kossin said. “All of these behaviors are ultimately linked to the warm water that these storms are sitting on top of,” he said. “The water is warm because the planet is heating up.”

Hurricane Erin is whipping up the Atlantic Ocean at speeds over 100 miles per hour. The trajectory of the storm has it staying out to sea, though many effects will be felt close to shore and on land. And some of those effects are made worse by global warming.

Overnight on Friday, Hurricane Erin ratcheted up to a Category 5 storm, from a Category 1, becoming one of the top five most quickly intensifying hurricanes on record. As the planet warms, scientists say that rapidly intensifying hurricanes are becoming ever more likely.

"It’s a very easy set of dots to connect,” said Jim Kossin, who worked at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration as a hurricane specialist and climate scientist before he retired. “These rapid intensification events are linked pretty directly to that human fingerprint.”

According to the National Hurricane Center, rapid intensification is an increase in a storm’s sustained wind speeds of at least 35 miles per hour in a 24-hour period. Between Friday morning and Saturday morning, Hurricane Erin’s wind speeds increased by nearly 85 miles per hour, peaking at 161 mph.

Daniel Gilford, a climate scientist at Climate Central, a science communication nonprofit, likens hurricanes to the engine of a car. “They need some fuel source in order to spin, and the fuel source is the ocean surface,” he said. “So as the temperature of the ocean surface goes up, that adds more fuel that these storms can use to intensify.”

For over a century, greenhouse gases emitted by human activity have trapped heat inside the planet’s atmosphere. A recent streak of record-breaking temperatures crowned 2024 as the hottest year on record.

By May of 2024, super marine heat waves had turned nearly a quarter of the world’s ocean area into bath water, and this year’s Atlantic Ocean remains warmer than average. Earlier this summer, forecasters anticipated a busier than usual Atlantic hurricane season because of this lingering heat, along with other regional factors. Erin is the first named storm to become a hurricane this year.

As a storm moves across warm oceans, it gathers more fuel and becomes stronger. Because warmer air can hold more moisture, hurricanes in hotter conditions can also carry more rain.

According to Climate Central’s analysis of the storm, human-caused climate change made the warm water temperature around where Erin formed 90 percent more likely. The group’s early estimate, using a statistical model developed by NOAA, also found that the extra heat could drive 50 percent greater damage, like tidal erosion and flooding, to coastal areas.

Other features of storms have been exacerbated by the warming planet, too. As polar regions melt and sea levels rise, Dr. Gilford said, the rising tidal base line means that any coastal flooding from storms becomes correspondingly larger, too.

During Hurricane Sandy, floods were four inches deeper than they would have been without sea level rise, according to a Climate Central paper published in the journal Nature. “That doesn’t sound like a lot, but four inches could be the difference between over topping the bottom floor of a building or not,” he said.

After intensifying, Hurricane Erin grew a second larger eyewall, which is the meteorological term for the thick ring of clouds at the cyclone’s center. Hurricanes that go through an eyewall replacement cycle are larger in size but tend to have weaker wind speeds.

As of Wednesday afternoon, Hurricane Erin was 530 miles wide, an expanse that would smother New England. While the storm’s strongest winds aren’t expected to reach coastlines, the powerful waves and riptides that are generated will.

Faster intensification makes eyewall replacement more likely, Dr. Kossin said. “All of these behaviors are ultimately linked to the warm water that these storms are sitting on top of,” he said. “The water is warm because the planet is heating up.”

Last edited: